Note: I am drawing heavily on this excellent article about debanking by Patrick McKenzie at his Bits About Money newsletter/website. It’s quite long but very very informative. I cannot stress enough that you will learn a lot from it - and he has a wry sense of humor that makes even the driest finance topic interesting.

There’s a famous saying that once is happenstance, twice is coincidence and thrice is enemy action. When it comes to Bank of America debanking conservative/Trump adjacent folks we are on at least thrice.

There are probably other examples, but these three showed up with almost zero searching by me. But even so, they may not be technically lying.

The WSJ wrote something about it (archive) that delicately hints at the issues:

Banks are vulnerable to allegations of political bias because they typically don’t explain why they close customers’ accounts.

Banks are required by federal laws including the Bank Secrecy Act to keep tabs on what their customers are doing with their funds and to ensure that they aren’t facilitating any criminal misconduct.

Transactions that look suspicious are supposed to be flagged in banks’ back offices. After enough red flags go up, banks often close the relevant accounts. The number of these so-called suspicious-activity reports has more than doubled between 2014 and 2023.

The following paragraph to that excerpt talks about the other high profile debanking area - crypto. I’m not going to get into the crypto bit though you can follow the breadcrumbs quite easily for that too.

The Debanking Mechanism

I’m going start this at the bottom with the bit that the debanked can see. The key to the eventual mechanism for the debanking is almost certainly this: “Transactions that look suspicious are supposed to be flagged in banks’ back offices. After enough red flags go up, banks often close the relevant accounts”

From the Patrick McKenzie article I mentioned in the note - you did skim read it, right? - there are a few paragraphs explaining what a is:

[T]he bank looked into their account after a transaction was flagged as suspicious. This generally happens because an automated system twinged on it. Most of the so-called “alerts” are false positives, but banks are required to have and follow a procedure to triage them. That procedure is typically “Send a tweet-length summary of the alert to an analyst and have them eyeball things.” Every bank needs at least one person triaging alerts; the largest banks have thousands.

What if the analyst, on the basis of their training, experience, and data available from the alert system and from the account history they can access, decides that a transaction has… more than nothing irregular about it? Then they compose a specially formatted memo.

That memo is called a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR). The bank files it with FinCEN, via a computer talking to a computer after the analyst pushes some buttons. Then the analyst goes back to triaging incoming alerts.

…

A SAR is not a conviction of a crime. It isn’t even an accusation of a crime. It is an interoffice memo documenting an irregularity, about 2-3 pages long. Banks file about 4 million per year. […]For flavor: about 10% are in the bucket Transaction With No Apparent Economic, Business, or Lawful Purpose. FinCEN has ~300 employees and so cannot possibly read any significant portion of these memos. They mostly just maintain the system which puts them in a database which is searchable by many law enforcement agencies. The overwhelming majority are write-once read-never.

Now the catch is that all this took a human or two perhaps 30 minutes to an hour to triage and then analyze. This is expensive. Assume 1 hour total triage/analysis time and a single employee equivalent (we’re munging together the triager and the analyst in this) can handle 40 a week or 2000 a year (50 weeks of 40 hours plus 2 weeks of vacation etc.). At half an hour that’s 4000. Banks in total file 4 million of these. That’s 1000 employee equivalents being paid a decent salary - probably 100k/year when you include employee taxes, healthcare etc. So between all the banks filing these SARs costs the banks $100,000 x 1000 = $100,000,000. $100 Million is a decent chunk of change. B of A, as one of the larger banks, is probably on the hook for a good 10% of that which implies a $10M salary expense and around 400,000 SARs. B of A undoubtedly wants to keep this cost down, and one way to do that is to have a policy to debank people who hit a threshold number of red flags aka SARs.

Thus as you read more of the McKenzie article it becomes clear that “enough red flags” may in fact be any number greater than one, unless your name is Biden. I have an online friend who used to work in this process at one of the other big multinational banks who describes the process like this1:

I used to file SARs. It's not an automatic "two and you're out" kind of thing. The choice to debank a person is made by the bank, not the feds, and for [bank], at least, they'd take four before they'd start considering more drastic action. (FYI, this is why I was really pissed when it came out that Hunter Biden had 250 SARs and still had bank accounts.)

Ultimately, the SARs exist so that when someone gets arrested for fraud, the bank can say "We weren't complicit! See, here's where we noted his activity was suspicious."

I should note that my job was to investigate automatically or manually flagged activity and investigate to determine if a SAR was appropriate. The computer says "This account cashes a lot of checks and deposits cash amounts near the reporting threshold several days in a row." looks Yeah computer, it's a grocery store. Or "this guy came in to deposit $32K of cash and said it was agriculture proceeds." Hmm ... well, he owns about 8 acres in Idaho, and the USDA says you can get $4K per acre of potatoes, and he immediate used the money to pay off a signature loan, so it's probably legit.

My guess is that the other big multinational bank has debanked fewer conservatives because it has a higher threshold for SARs. Hence the other big multinational bank is not getting Xeets of unhappy former customers and thus is not facing quite the same volume of questions about its debanking policy. The experience of many people I know who have (had) B of A as their bank is that they are cheap scumbags who have zero interest in spending money to make a customer experience more pleasant, thus I would be extremely unsurprised if B of A debanks you as soon as you hit two SARs or even one SAR and a bunch of events that need triaging.

There’s a catch though. The bank is legally forbidden to mention that it is debanking you for suspicious-activity reports (SARs) because it is legally forbidden under US Federal law to mention SARs to anyone (including other people in the bank):

No, the bank cannot explain why SARs triggered a debanking, because disclosing the existence of a SAR is illegal. 12 CFR 21.11(k) Yes, it is the law in the United States that a private non-court, in possession of a memo written by a non-intelligence analyst, cannot describe the nature of the non-accusation the memo makes. Nor can it confirm or deny the existence of the memo. This is not a James Bond film. This is not a farce about the security state. This is not a right-wing conspiracy. This is very much the law.

If you work at a regulated financial institution, in the U.S. or any allied country, you will be read into SAR (and broader AML) confidentiality within days of joining. You will be instructed to comply with it, very diligently. If you do not, your employer may suffer consequences. You personally are subject to private sanction by your employer (up to and including termination) and also the potential for criminal prosecution. If your trainer speaks with a British accent, they will phrase the offense as “tipping off.”

It’s not just illegal to disclose a SAR to the customer. It is extremely discouraged, by Compliance, to allow there to be an information flow within the bank itself that would allow most employees who interact directly with customers, like call center reps or their branch banker, to learn the existence of SAR. This is out of the concern that they would provide a customer with a responsive answer to the question “Why are you closing my account?!” And so this is one case where in Seeing like a Bank the institution intentionally blinds itself. Very soon after making the decision to close your account the bank does not know specifically why it chose to close your account.

This is not something most people know. More importantly the process of debanking regular retail customers (small businesses or individuals) by their banks for hitting the magic second SAR is entirely automated and there is no one that the individual concerned can talk to because (see quote above) the bank institutionally takes care to ensure that no one knows why the debanking decision was made.

So why would people like John Eastman, Eric Prince and General Flynn be debanked? In other words, why did some part of B of A generate SARs about them?

Well again there’s some possible cover. SARs are often generated for transactions with “politically exposed people” (PEPs), which is another term of art that McKenzie explains:

Politically Exposed Person (PEP) is a term of art in Compliance, arising from Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) reporting requirements. It means a national-level senior official, most typically in U.S. usage, one attached to a foreign government. Quote: “The Agencies do not interpret the term ‘politically exposed persons’ to include U.S. public officials.” (Like many financial regulations, the U.S. has intentionally caused its concern with PEPs to metastasize to aligned countries. In some of those countries, financial institutions are obliged to treat from-their-perspective-domestic senior political officials/etc as PEPs.)

PEP status also attaches to the close family members and close associates of a PEP. Who is a “close associate”? Write down your understanding of that, run it by your regulator, and then comport your affairs consistently with your written understanding. Lots of banking regulation works like this: plodding, iterative development of internal policies, with occasional spot checks on performance under those policies, including as part of scheduled bank examinations.

PEPs are believed to present elevated money laundering risk. Some of them control national resources directly, and others may be at risk of e.g. bribery.

There is not an official regulator-blessed list of which positions are presumptive proof of PEPiness. This is one of those things that banks need to write down in their procedures then run past their regulator, who will either say “Sounds good! Definitely EDD those PEPs!”, or “I dunno. I know it’s a schlep but you’ll want to grep more PEPs.”

Bank of America certainly has a list of PEPs, though they almost certainly won’t tell anyone who is on that list. While John Eastman, Erik Prince and Mike Flynn should not be on that list (see “not including U.S. public officials” above) all three could easily have had interactions with public officials in other countries that are on a PEP list.

We know from a couple of years ago that Nigel Farage was a PEP that caused UK bankers concern - in addition of course to him being debanked himself. One suspects that there are many people in Europe, Africa and the Middle East who are PEPs according to various US banks and of course the “family members and close associates” rule likely extends that to companies, foundations and charities that they are associated with and so on. Quite possibly entire political parties such as AfD are included. Now the defense the bankers have is that these politicians are “far right” terrorist adjacent or that they are suspected to be corrupt - a designation that would hit Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu for example - but the bigger defense is not expecting anyone except some federal regulators to see the list in the first place.

So if you, a person with a conservative/Trumpian viewpoint accept, say, a speaking engagement at a conference in Israel (or Hungary or…) that is organized by some entity associated with a PEP then you will get a payment of speaker fees from that entity and that will generate a SAR. If you are unlucky you’ll also submit an expense claim for travel etc. to that entity and that will be paid separately, which generates a second SAR and the bank’s automated risk management computers decide to debank you. Or if you don’t get a second SAR that way, perhaps you speak at another conference a year later and get a SAR for that. Or you get book royalties because a PEP associated organization translated a book of yours and that payment triggers a SAR. Or… There are so many possibilities for a foreign PEP associated entity to legitimately pay you for something that could trigger a SAR.

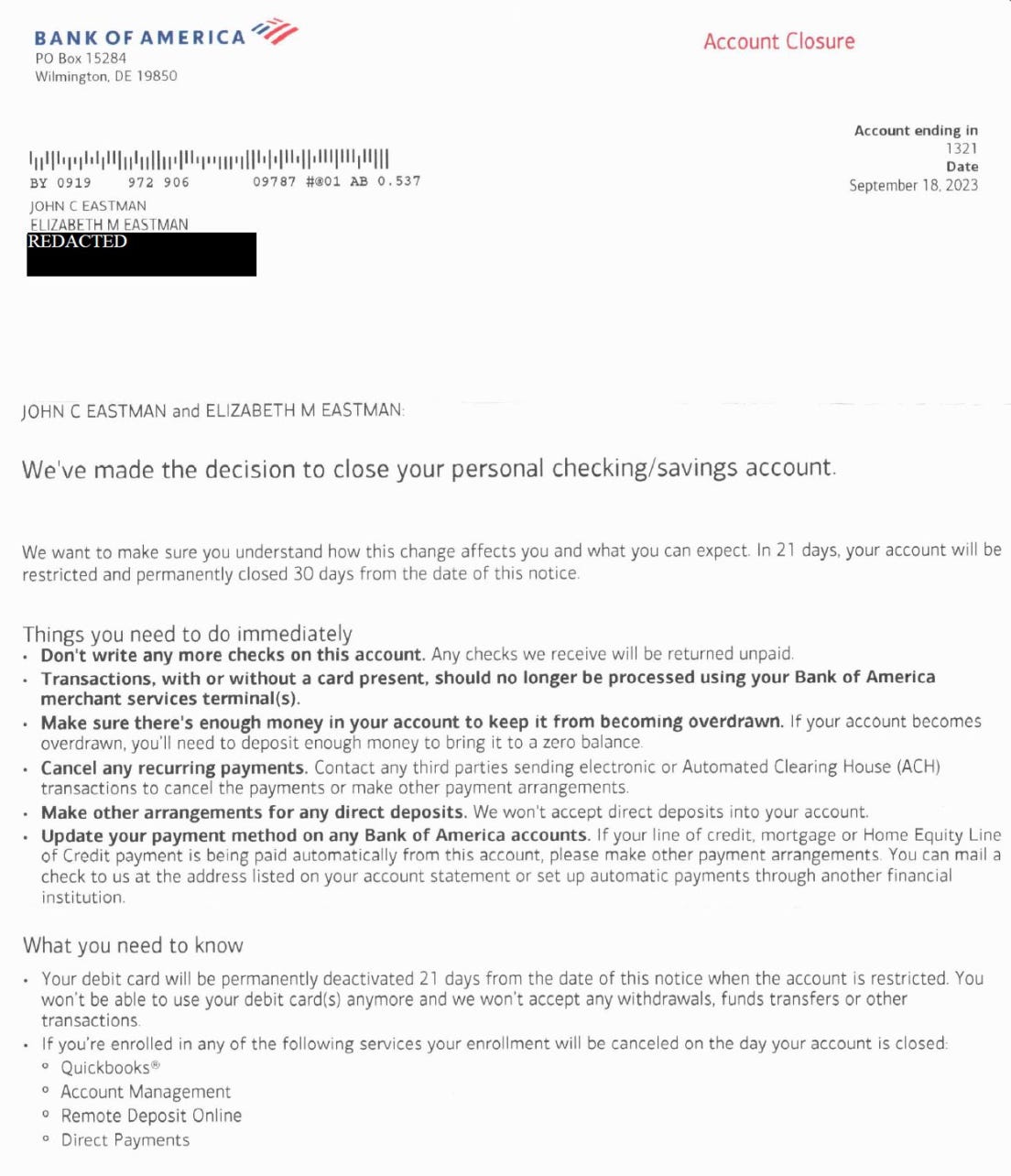

None of the above is actively intentionally malicious. It may seem that way. In fact when you get an automated letter like this, it will almost certainly seem that way because there is zero explanation

When you call the number to complain, you will get a run around because (see above) the call center staff have not been told why your account has been shut, and if they had been told (or you managed to talk to someone who knows) they would be legally prohibited from “tipping you off”. That run around will very definitely seem malicious even if, from the bank’s point of view it’s just standard procedure no different from handling a shifty bodega or gang related debt collector.

The key is that people like John Eastman, Erik Prince and Mike Flynn are solidly part of the law abiding middle class and don’t expect to be treated like a bodega in the bario. They expect to see evidence that they can challenge in a court of law or similar and assume that failure to explain or allow for an explanation is ipso facto proof of maliciousness, which is not necessarily true.

And note that AML regulations explicitly require banks to follow the money trail so if person A gets $100,000 and then makes several $10,000 payments to person B then person B is assumed to be laundering money for/from person A. A classic example of this would be certain people named Biden writing checks to other people named Biden that are purportedly repaying a loan for which there is no trace. Hence Prince’s ex-wife gets her account closed because she could be laundering Prince’s ill gotten gains and so on. Oddly if your name is Biden then none of this AML tracking applies, but it absolutely applies to people named Prince or Eastman.

From Coincidence to Enemy Action

However it doesn’t take much to exploit this legally required secrecy and be actively malicious.

For example a politically progressive bank employee in the right department could add entirely legitimate foreign entities who are not in fact in anyway corrupt or sleazy to a list of PEPs or other similar confidential indicators of badness. Likewise even domestic entities that, say, the SPLC puts on a list of badness could be included. All they would need in the latter case is to have a bland memo passed and agreed on in some relevant meeting that cited a news report that the DoJ or some other federal body was concerned about X and that the SPLC had a list of people / organizations that were X. Then anyone who pays or is paid by any entity on the list gets a SAR. And probably another one from either the same entity or another similar one. These entities will in fact be perfectly harmless because the SPLC list is created by progressive activists with axes to grind who are quite happy to name the Heritage Foundation a far-right extremist terror sympathizer.

And then there are the feds. Who have previous on this sort of thing under Obama with Operation Choke Point. From the McKenzie article again:

If you have that intuition, you are apparently not creative enough to have worked as a lawyer in the Obama admin DOJ. No, their thought was that if you provide rails which facilitate fraud, such as giving a fraudster a bank account, you are affecting a financial institution: yourself. And so, the DOJ can go after you, for self-harm. Note that you do not need to lose money, oh no, the DOJ can also go after you because the way you affected yourself was to cause your regulator to like you less. When you settle with the DOJ, it will extract an enforceable promise in writing that you will stop your campaign of self-harm, and also stop banking specifically enumerated industries, like payday loans.

I realize that this sounds unlikely. The following is a direct quote (expanding acronyms) from the DOJ Office of Professional Responsibility, in the report (pg 16) where they exonerated DOJ lawyers.

As more fully explained below, the [Consumer Protection Branch] has relied on the “self-affecting” theory, as well as additional theories of liability, in three cases arising from the Operation Choke Point initiative.

…

As it turns out, the Obama administration had many diverse policy preferences.

It wasn’t particularly in favor of guns, for example.

Gun sellers don’t use banks in the way that debt collectors use banks. They do not routinely trick customers into the gun-for-money transaction. They don’t make particularly intense use of ACH pulls (confidence: 99%, on general industry knowledge) and don’t have particularly high dispute rates (confidence: 95%, same).

But regulators, having discovered that “reputational risk” attached to anyone you didn’t like with nary a whisper of complaint, believed that banking gun sellers was high-risk. Haven’t you read the newspapers? School shootings. Do you want any of that sticking to you? You are imperiling your good name, and therefore the stability of your deposit base, and therefore your bank, and therefore the insurance fund, by accepting the business of gun sellers.

…

Emails sent within the FDIC and DOJ were routinely archived, and banks (of course) keep copies of correspondence from their regulators. Those emails said what they said, and what they said was pretty damning.

For example, the Department of Justice’s internal Six Month Status Report On Operation Choke Point (excerpted in Congressional reporting) said:

Finding substantial questions concerning the legality of the Internet payday lending business models and the loans underlying debits to consumers’ bank accounts, many banks have decided to stop processing transactions in support of Internet payday lenders. We consider this to be a significant accomplishment and positive change for consumers . . . Although we recognize the possibility that banks may have therefore decided to stop doing business with legitimate lenders, we do not believe that such decisions should alter our investigative plans.

Not once, not twice, not a handful of times, not a loose confederation of rogue examiners. Three of six regional directors of the FDIC offices told the OIG that they understood Washington to want payday lending discouraged and two of them said there was an expectation to, in the words of the OIG, direct institutions that facilitated payday lending to “pursue an exit strategy.”

Does anyone think that the same DOJ lawyers and Treasury/FDIC etc. regulators might not have learned from being hauled over the coals regarding Operation Choke Point and said similar things regarding notable conservatives/Trumpers in ways that were not as easily archived for later discovery? If that’s the case then B of A is going to find it hard to explain why it debanked people to the relevant congressional committee sometime later this year.

Of course they may also have been just as arrogant as before and put the same things in memos and emails that B of A has copies of. My guess is that B of A’s legal department are checking X for people like Prince and Flynn who report that they were debanked and then running searches on emails to/from non BofA addresses referring to these people. When the relevant congressional committee hauls B of A execs up to explain themselves the execs will be only to happy to point to DoJ/regulator emails telling them that, for example, pro-life organizations are terrorist enablers and that anyone who receives a payment from them is therefore to be considered either a terrorist or an enabler themselves.

Is B of A Lying?

So when Bank of America says they close accounts for political reasons and don’t have a litmus test they could be telling the literal truth.

They don’t have a policy to debank conservatives or Trumpers.

They have a policy to debank people with retail accounts who receive more than one SAR2 regarding their bank account.

They have policies to generate SARs when accounts send money to or receive it from accounts associated with individuals or organizations that are designated suspicious.

They have policies that state that PEPs are suspicious and that (domestic) extremists are suspicious along with others that talk about people named Guido or Putin or containing the words Sinaloa, Cryptocurrency and so on.

Probably they have memos from regulators that say that they should have these policies and which will likely mention to laws and federal regulations that apply.

They have lists of PEPs and Extremists.

Unfortunately those lists happen to include many people and organizations that are conservative/libertarian/Trumpian and few if any that are “progressive”.

And so yes, sadly, they debank conservatives and don’t debank progressives but there is no explicit policy to debank conservatives or Trumpers.

If the lists of “bad people” end up including, say the SPLC, Antifa or ActBlue then the exact same machinery will end up debanking prominent people on the left - though probably not ones called Biden, Clinton or Obama

Fixing this

I hope this post satisfies the “why it’s there” requirement of Chesterton’s Fence3. One of the problems with fixing this is that it has evolved over decades and we actually do want banks to not enable real criminals.

[Aside: A large part of the problem with crypto is that it seems to me that about 90%4 of crypto transactions are criminal, so while we do not in theory want to block crypto, blocking crypto ends up blocking a lot of what governments consider criminal activity without blocking much legitimate activity. Hence blocking crypto is a relatively low impact way of stopping all kinds of crime.

Furthermore if you are a bank and thus, almost by definition, risk averse, you will tend to feel that the potential downsides to you as a bank of handling crypto are way way worse than any potential upside because the upside of lots of profit will tend to go to the crypto bro, while you are left holding the bag when the crypto bro turns out to actually be a fraud bro. As McKenzie points out it is very hard for a banker to tell the difference, initially, between legit crypto business and fraud/money launderer and thus as a risk averse banker it is far easier to simply have nothing to do with it.]

The most obvious thing is to remove the secrecy. Sunlight will provide a lot of clarity.

This starts with removing the secrecy of SARs. As another online friend noted, the whole not “tipping off” thing is kind of rendered moot when you get your account closed after one or two of them. In fact I think it would generally help the innocent to be informed that transaction X (or A,B,C…) triggered a SAR. Innocent people could then challenge that SAR and explain the transaction X was “speaking fees from this conference - see BBC report here” or that “monthly transfers A B C are child support as mandated by this court settlement here”. Now it might cause some actual criminals to try and modify their behavior but it could potentially put the scare on some borderline sorts who aren’t intentionally criminal but hadn’t realized that allowing Ahmed to receive money from Lebanon via your bodega was not good.

One of the good things in the UK is that you can request the bank show you all documentation they have about you, albeit with some personal details redacted, and (AIUI) they are required to provide the reason they are debanking you. Some of this was prior to the Farage affair but it was strengthened in response to that.

That openness would certainly help crypto bros understand why they are debanked and perhaps help them figure out how to structure their personal banking affairs so that those personal accounts are not mistakenly tagged as crypto business related ones. It should be noted that thanks to crypto fraudsters like SBF and co. there are legitimate reasons for banks to be skeptical of crypto businesses and that crypto fraudsters have in fact used their personal accounts to shift money around for their business (and vice versa). If banks told crypto bros that “doing A, B or C with your personal account makes it look just like an illegitimate extension of the crypto business you founded” then the crypto bros can decide whether they want that or not. Right now they, and everyone, are forced to guess what activities trigger review.

Relatedly banks should be required to point to regulatory communications when stating that activity X is problematic. Right now a lot of this regulatory guidance is of the wink, wink, nod, nod sort where regulators write broad guidance about topic T, bank compliance departments ask whether activity Q counts in a phone call and the regulator says “Sounds good! that’s the sort of thing it covers” but there’s no record of it. If regulators are required to put in writing that activity Q is frowned upon because of topic T then everyone knows and, if necessary, can write to their congressman and complain. Regulators hate this, which is why they don’t do it. But regulators are supposed to be civil servants not civil masters. Allowing them to obfuscate and hide gives them mastery, forcing them to state on the record makes them servants.

One very specific requirement is that banks and regulators should publish the sources of the data they use for their lists. Thus if a regulator (or DoJ person) says we think the SPLC list of domestic terrorists is good, then that has to be visible somewhere so that the pro-life campaigners etc. on that list can raise a stink before they get debanked. If a regulator says “you need a list of domestic terrorists, go find one” without being specific then the banks need to document why they picked the SPLC and how they whitelisted the false positives on it. If the list comes from the FBI or similar and is flagged as secret, then some other party - the courts? congress? - needs to review it to make sure it is fair.

It looks like DOGE and Trump are all in favor of taming the federal civil service and making them servants again. A requirement of openness, with teeth such that evading it is a reason to be fired for cause, would help in many areas and that absolutely includes banking and financial regulation.

BTW that friend thinks that the McKenzie article is generally correct and has a fun additional anecdote about the sort of thing that gets flagged and requires an analyst to investigate:

Another fun one of the last was a woman who cashed a check for two males names. About an hour of research later, I could solidly establish that it was a mom cashing checks for her 10 and 12 year old sons who raised pigs for the local fair.

It occurs to me that if you are a bank that pays analysts in ways similar to call center workers where you get dinged for spending too long on a case, then this sort of thing will simply get flagged for a semi-autogenerated SAR memo after 10 minutes instead of spending an hour to work out that it is a legitimate thing. Then if you have a policy of 2 SARs to debank when the same thing happens the following year she’s debanked.

It could be more than 2 or even more than 4, but the point remains, it’s a small number unless your name is Biden

Before you rip something down understand why it was put there - https://theknowledge.io/chestertons-fence-explained/

Number derived from my posterior, but includes all those people using crypto to try and evade taxes and whatever the number is, it is a significant fraction of all crypto activity

Hi, I'm the friend. A few more loosely associated thoughts:

One way to sell banks on changing SAR confidentiality rules is that it can help them. I had a case where the customer had picked up a gambling addiction. He'd drained his accounts and was accumulating credit card debt. He was also an account manager at another one of the big multinational banks. To alert that bank that one of their employees was a major fraud risk would have been illegal though. And our job wasn't to punish people for being bad with their finances but to catch money laundering. No SAR.

To take up a major issue of the day, I'd see the impacts of illegal immigration in potential fraud cases. Legitimate banks require proof of identity, so one citizen/ legal resident would cash a bunch of checks for his coworkers and then pay them back with a peer-to-peer service like Venmo, Zelle, or CashApp. In fact, part of what triggered the investigation of the mother cashing her sons' checks was that their last name was Hispanic.

The banks are woefully unprepared for how people use peer-to-peer banking services. Another common pattern was the person using P2P services to run a business without needing to comply with all the rules for small business accounts. But our job was anti-money-laundering and fraud investigation, not tax evasion, so no SAR.

A fun story on how banks aren't quite used to the modern world: one account was flagged because this twenty-something was withdrawing tens of thousands of dollars, but his listed job was waiter. I look at the deposit history: several hundred dollars every day from Google Adsense. I google him, and yep ... he's a TikTok/YouTube star. No SAR.

Another fun no SAR case: woman comes in and deposits several thousand dollars in small bills. Teller flagged it as suspicious. Listed occupation? Exotic dancer.

The most sad cases were the elder abuse ones. These not only got a SAR but another elder abuse form. I did see one happy ending though: adult daughter took out a $20K signature loan pretending to be her elder mother. Mother went to the bank, and the tellers helpfully asked why she hadn't been making payments. "What signature loan?" She replied. Well, in the three days between the branch filing the report and it getting to me, there was a $20K transfer from daughter's account to mother's. Go little old lady!

Call me whatever but debanking is criminal and wrong, period.